New qSEL Study Quantifies Important Considerations for Heating Decarbonization in the United States

Read the full article published in Joule.

Greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation get a lot of attention, but the 12% of nationwide emissions from burning fossil fuels in buildings cannot be overlooked, particularly because they are the largest emissions source in many places. For example, in New York State and New England, fuels used in residential and commercial buildings account for more than 30% of total emissions; in New York City, the number reaches 42%. The main culprit is space heating.

What is the best way to eliminate fossil fuel usage for heating buildings? The approach getting the most attention is to go “All-Electric”: Replace all existing fossil fuel furnaces and boilers with electric heat pumps and dramatically scale up wind and solar electricity supply. This isn’t your traditional electric resistance heating with obscene monthly electricity bills. A heat pump is the same technology that provides the vast majority of air-conditioning and can achieve a coefficient of performance – the amount of heat delivered per unit electricity consumed – of well over 3 on average and more than 5 at times.

That sounds pretty good and straightforward. Maybe a bit daunting considering the tens of millions of existing buildings, but we already know decarbonization will require mass mobilization. So, let’s get going, right?

This story is missing the significant potential capacity implications of widespread heating electrification. Whereas air-conditioning generally drives current peak electricity demands, winter indoor-outdoor temperature differences can be much higher in much of the U.S. And in a cruel trick of thermodynamics, a heat pump’s heating capacity and COP decrease as the outside temperature decreases and the heat is needed most. “Cold climate” heat pumps are improving significantly, but even the most advanced prototypes operate with low-temperature COP less than half the rated COP. The largest impacts are likely to be in electricity distribution systems, which can be the most expensive part of the vast machine that supplies electricity to buildings.

To better understand these effects and their implications for energy planning, we recently quantified the relative capacities of existing fossil fuel and electricity delivery infrastructure and computed the load effects of heating electrification for all U.S. residential and commercial buildings. The study by Michael Waite and Vijay Modi – published online December 20th in Joule – investigated current state-of-the-art heat pumps, potential achievement of Department of Energy performance targets, and dual source systems that maintain existing fossil fuel heating equipment in addition to new heat pumps (systems sometimes called “hybrid heat pumps” or “dual fuel heat pumps”). We developed a method that uses several disparate public datasets, applied statistical techniques and several heating electrification models to compute loads down to the census tract level. With over 72,000 census tracts in the U.S., this represents a uniquely high spatial resolution study and a new open dataset that will benefit future research in this area.

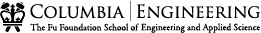

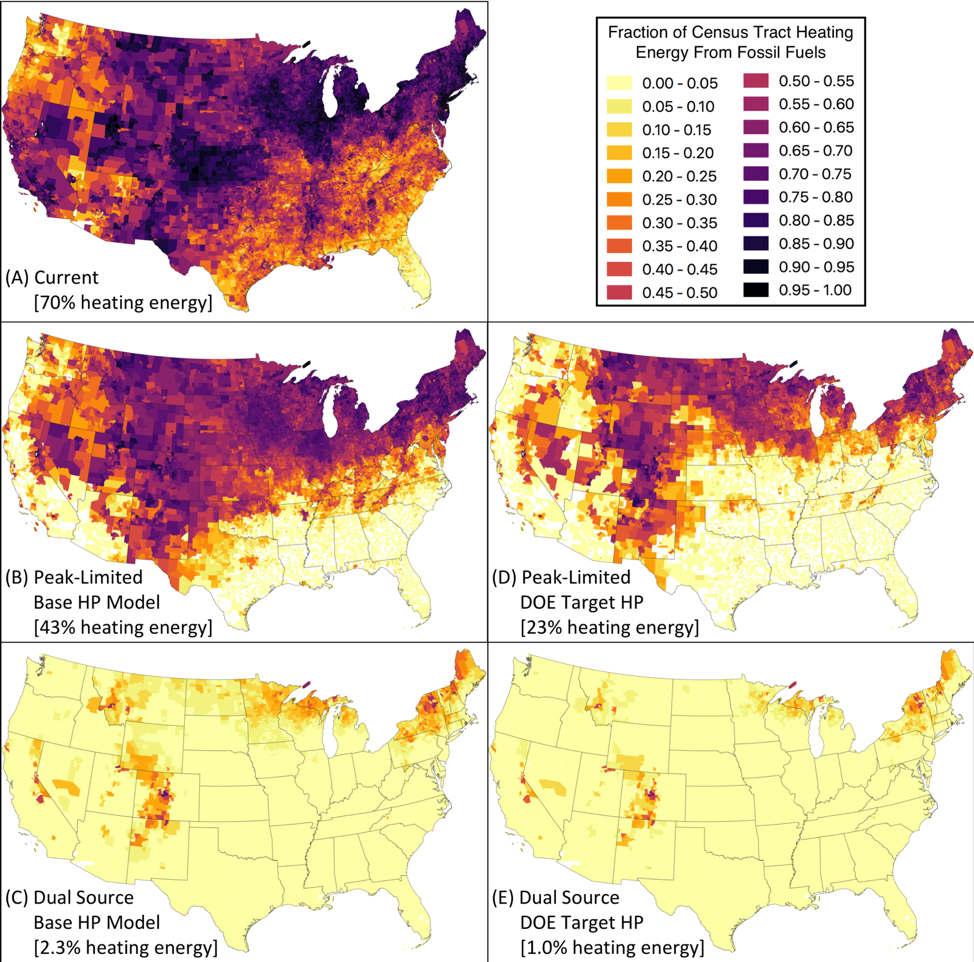

We first wanted to get a handle on the existing differences between the delivery capacity of fossil fuel (which currently provides 70% of all space heating energy) and electricity systems. The heating fuel mix (natural gas, fuel oil, propane, and some existing electric heating) is different across the U.S. and in urban and rural areas; for the time being, we looked at the total fossil fuel demand and will break down the regional effects in future research. We computed the aggregate nationwide fossil fuel delivery capacity to residential and commercial buildings to be 91% greater than the corresponding electricity capacity; however, as the map at the top of this post shows, the ratio of peak demands for fossil fuels and electricity vary considerably with most of the Northeast, Upper Midwest and Rocky Mountains seeing ratios exceeding 3 or 4.

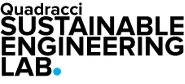

Given that the energy transition will largely take place in a context of robust existing infrastructure, understanding this scale is important to evaluating paths forward. So, we next looked at the electricity load effects of the all- electric heating approach using current state-of-the-art heat pumps. As discussed above, we get some benefit from the high COP of heat pumps, but still compute an aggregate nationwide “electricity peak ratio” of 1.70 (the ratio of the new peak electricity demand with all electric heat pumps to the current peak electricity demand, a proxy for increased electricity delivery capacity). The map below shows that, once again, the effect is highly dependent on where you are: 1/3 of all census tracts (which represent 45% of nationwide heating energy demands) and 23 states as a whole see electricity peak ratios of more than 2, suggesting more than double existing electricity delivery capacity would be needed in these areas.

As we note in Joule, “Capacity expansions of the scale implied by these results are not necessarily problematic if needed to meet new demands. However, the economics of such an investment are likely to be largely dependent on the infrastructure’s capacity utilization.” Unfortunately, what we find in our analysis is that because heating demands vary so much during the year and the coldest temperatures occur so infrequently, these increases in electricity load would be equivalent to fewer than 50 annual full load hours on average. This is a highly expensive proposition for new infrastructure, but it suggests an alternative transitional path.

We propose that we can make use of existing fossil fuel infrastructure to avoid a large buildout of electricity delivery capacity while dramatically reducing fossil fuel usage: Dual source systems (DSSs) that use new heat pumps, but also maintain some existing buildings’ fossil fuel-based heating for only the coldest weather. The same causes of the anticipated underutilization of new electricity capacity in an all-electric heating approach mean that the need for fossil fuels in this scenario would be highly limited, less than 3% of all heating energy. If future technologies achieve the performance targets of the Department of Energy, heat pumps can replace even more fossil fuel-based heating and even further reduce the fossil fuels used in DSSs. The figure below shows several maps with fossil fuel needs under various scenarios that do not increase any census tract’s peak electricity demand and compare them to the current situation.

Perhaps counterintuitively, leveraging existing fossil fuel infrastructure can actually help transition away from fossil fuel dependence for heating while also reducing the total heat pump capacity needed. We should emphasize this infrastructure may not transport fossil fuels in the future if alternative fuels become part of the larger energy transition. Overall, based on the results of this study, we can classify three elements of a path away from fossil fuel heating without increasing peak electricity loads:

-

Approximately 1/3 of current fossil fuel heating capacity can be fully replaced with currently available heat pumps.

-

An additional 1/3 of fossil fuel heating capacity could eventually be fully replaced by future advanced heat pumps performance; fossil fuel usage could be dramatically reduced during this transition by using DSSs.

-

The remaining 1/3 of capacity would be very challenging to replace even with advanced heat pump technology, but by retaining “backup” heating capacity, the vast majority of space heating fossil fuel usage could be eliminated.

These results are promising, but point to further engineering and research needs, particularly for space heating in cold climates. These might include breakthroughs in heat pump technology, significant cost reduction and advanced installation methods for ground-source heat pumps, and the development of alternative fuels (including those produced from renewable resources). It is our hope that this study improves the understanding of the heating decarbonization challenge while also pointing to new opportunities to effectively meet that challenge.